Still the rain did not come…

Christopher Young

“It is not going to be easy to look into their eyes.” (1)

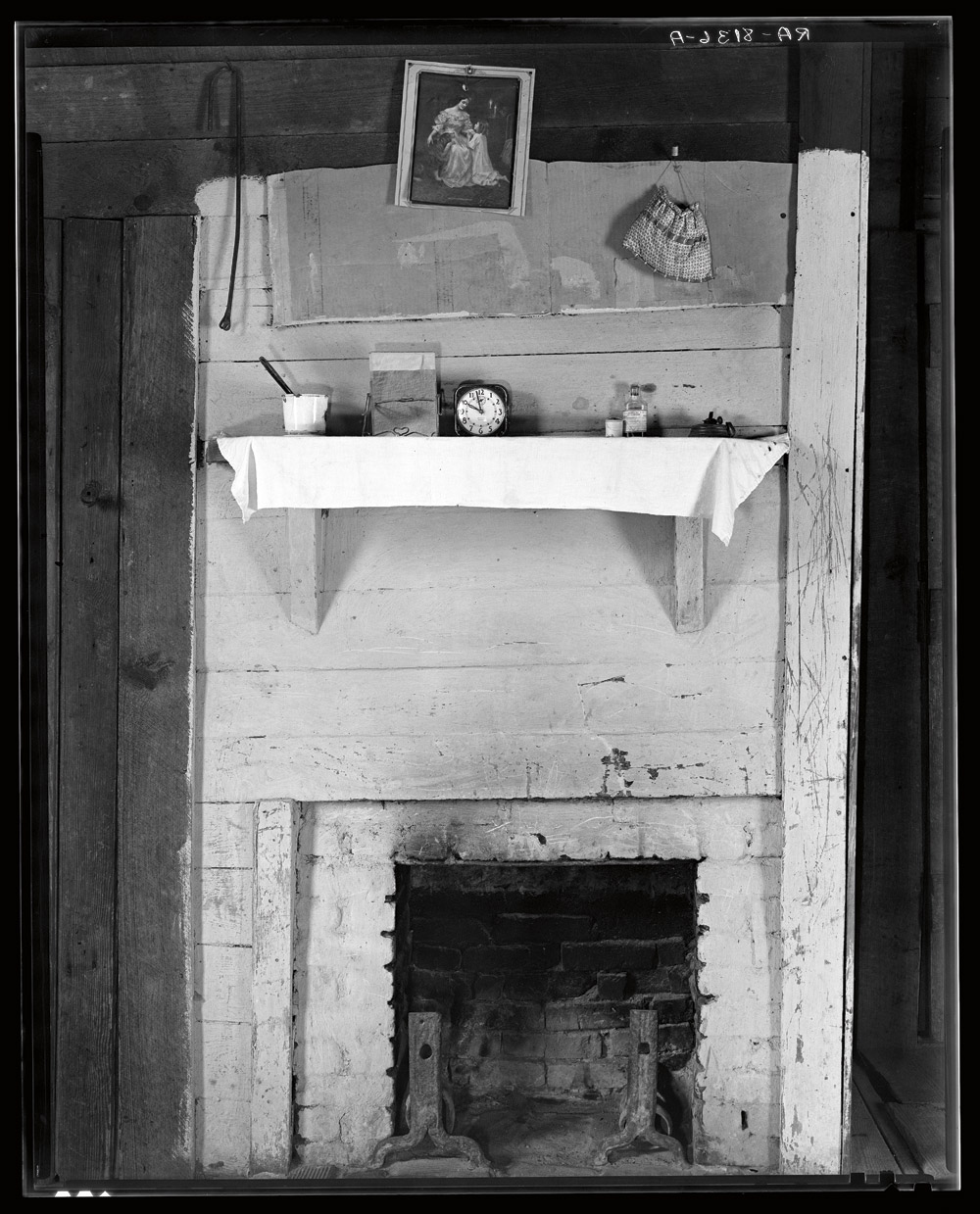

“… all the four rooms of this house where the [Burroughs] live are here at once each in its space and each in balance of each other in a chord … and of how all these furnishings and objects, within these rooms, are squared and enchanted as in amber.” (2)

In July and August of 1936, photographer Walker Evans and writer James Agee spent three and a half weeks in Hale County, Alabama working on a commission for Fortune Magazine.

The resultant article was to be published as part of an ongoing series in Fortune titled Life and Circumstances. (3)

This series of articles introduced corners of American life to business readers. Eric Hodgins, the managing editor of Fortune, thought that the plight of the white Southern tenant farmers as well as the health of the Southern cotton industy might interest his readers. (4)

“By July 7 [1936], it was a record 119 degrees [48.3°C] in parts of [North Dakota]. Fields were scorched brown and black … Grasshoppers descended on the region, their vast numbers consuming what little crops remained. By July 9, heat had killed 120 across the country … On July 11, the people of Mitchell, South Dakota, turned to prayer. Bells in the city’s 13 church towers tolled the signal to the people, 11,000 in number, to fall to their knees … Still the rain did not come.” (5)

As the drought and heat wave ravaged parts of the country, the pair focussed their project in on three families, staying with one of them, the Burroughs, for most of the time they were there.

The pair alternated with one of them sleeping in their car and the other sleeping on the wooden floor of the dog run in the house. (6)

After a while, Evans moved to a nearby hotel as he couldn’t tolerate the food, heat and insects (7) but Agee stayed on, living with the family.

“There are two stainless steel knives and forks with neat black handles which would have cost a dime apiece, and against what little we could do about it these are set at our places; but by actual usage they belong to the two parents … Almost no two of the plates, or cups, or glasses, or saucers, are of the same size or pattern. All the glasses except one are different sizes and shapes of jelly glass.” (8)

Agee’s observational writing is extremely thorough. He noted the smallest of details obsessively.

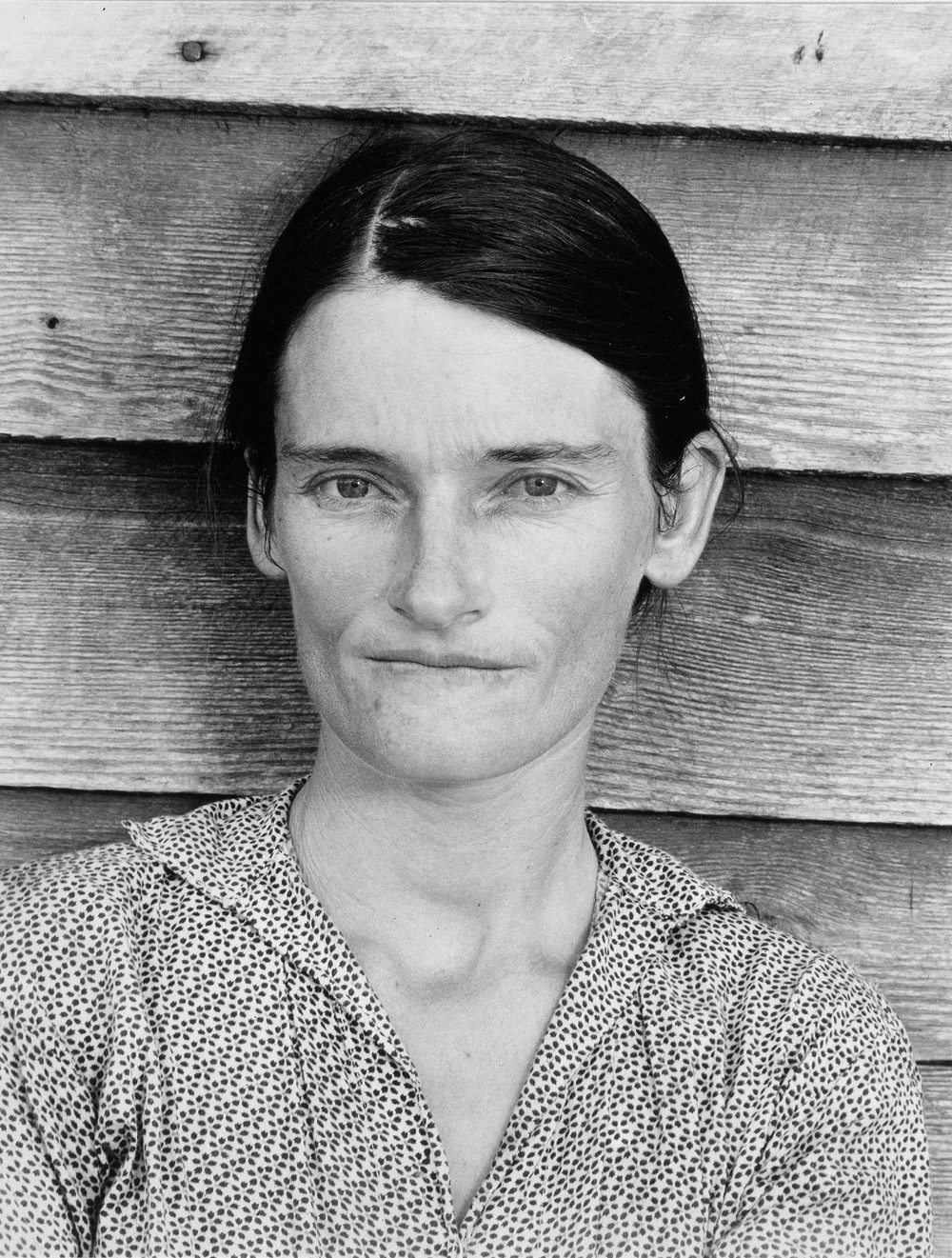

The intimate text also noted smells, his personal desires, in particular for Mary (Allie Mae Burroughs’ sister), as well as simple things like the insect bites he suffered.

“Just a half-inch beyond the surface of this wall … lie sleeping, on two iron beds and on pallets on the floor, a man and his wife and her sister, and four children … I know they rest and the profundity of their tiredness.” (9)

Combined with Evans’ images, the work paints an extremely thorough and compelling portrait of both the families and spaces.

“[Floyd] speaks, low, and is answered by both women; and a silence; and [Mary] murmurs something; and after a few seconds [Allie Mae] murmurs a reply; and there is a silence … in the darkness of the continent before the unwatching stars …” (10)

Left alone in the house at various times, both men were however quite invasive in how they carried out their project. Agee writes:

“No one is at home, in all this house, in all this land. It is a long while before their return. I shall move as they would trust me not to, and as I could not, where they here. I shall touch nothing but as I would touch the most delicate wounds, the most dedicated objects … in knowledge of those hidden places I have opened … those garments who I took out, held to my lips, took odour of, and folded and restored so orderly … I receive a strong shock to my heart, and I move silently, and quickly … In some bewilderment, they yet love me, and I, how dearly, them; and trust me, despite hurt and mystery, deep beyond making of such a word as trust … It is not going to be easy to look into their eyes.” (11)

Evans moved furniture around (12) and, it has been argued but vehemently denied by Evans, manipulated scenes (13) to suit his photographic purposes.

As the family worked, Agee and Evans stayed back at the house. The Burroughs assumed they were simply lazy, but later learned, through the book, that they were looking through their drawers. (14)

“‘Momma and Daddy didn’t know what they was doing. They was trying to help ‘em out. And they just wanted to write about how poor Momma and Daddy was … That was invading their privacy,’ Dottie [Burroughs, the youngest daughter of Allie Mae and Floyd] concludes emphatically. ‘They shouldn’t have done that.’” (15)

The article, as well as subsequent rewrites, was rejected by Fortune and a first edition of the book was only produced years later in 1941. Agee had insisted that the text be published unedited and this, combined with his insecurities about the content, had contributed to the delay.

It was hardly a success with mixed reviews and only 600 copies had sold by the time of Agee’s premature death at age 45 in 1955.

Following renewed interest in Agee’s work after his death, a second printing followed in 1960 and the book is now considered a classic.

Other than fleeting contact with Agee over a few years, the families were largely unaware of the book. Some only seeing it some 30 years later.

This is especially sad as Allie Mae Burroughs, an icon of the Depression era, spoke of the experience as if it were a family visit, mentioning that they were sad to see the pair go. (16)

There have been threats of legal action at various stages as the families supposedly only took part on the premise that the images wouldn’t be shown in the South and felt great shame at how they were personally portrayed. (17, 18)

There was resentment as those involved didn’t see any financial benefit from the experience. Neither from the book or print sales.

The families were under the impression that the project would help them escape their circumstances having initially met the two men whilst in Greensboro to seek assistance. (19, 20)

Evans had struck up a conversation with the three farmers in front of a courthouse where the men were seeking government relief. The initial invitation to visit the houses was supposedly due to the misapprehension that the pair were government men and they might be able to help the families. (21)

Revisits to the area by documentary crews, journalists and photographers have revealed a lot of animosity in the community about the project.

“She offered me some journalistic advice. ‘If you write something that’s a scandal on my family,’ she said, ‘you better give your heart to God because the rest of you belongs to me.’” (22)

However problematic the images and text may be, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is a fascinating insight not only into 1930s America but equally into the motivations and processes occasionally used by artists.

This text was written to support the Small Town project.

Walker Evans, Fireplace in bedroom of Floyd Burroughs’ cabin. Hale County, Alabama, 1936

Walker Evans, Allie Mae Burroughs, 1936

- Agee, J. & Evans, W. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1941. The book was published with all protaganists under pseudonyms. The text in square brackets has been changed to their real names.

- Ibid.

- The article was ultimately rejected by Fortune and was later published in book form in 1941.

- Thompson, J L., The Story of a Photograph, Walker Evans, Ellie Mae Burroughs and the Great Depression. Now and Then Reader LLC., 2012.

- Morris, E., The Case of the Inappropriate Alarm Clock (Part 1). New York Times, October 18, 2009

- Rathbone, B., Walker Evans – A Biography. First Mariner Books, 2000.

- Ibid.

- Agee, J. & Evans, W. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1941.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Thompson, J L., The Story of a Photograph, Walker Evans, Ellie Mae Burroughs and the Great Depression. Now and Then Reader LLC., 2012. Allie Mae Burroughs returned from an excursion one day with Agee to find that the furniture had been ‘moved all around’. It had been put back but not exactly the way she had it.

- Morris, E., The Case of the Inappropriate Alarm Clock (Part 3). New York Times, October 20, 2009. Errol Morris discusses at length the supposed insertion of an alarm clock into a particular image. This forensic-like examination includes such arguments that Agee’s detailed description of the scene doesn’t include a mention of a clock; the alarm clock is set for 8am (farcically late for a farmer); this particular style of clock was traditionally used by travellers; and that the clock was well worn on its edges implying it had travelled.

- Davidson, C., Let Us Now Trash Famous Authors. The Atlantic, April 2010.

- Ibid.

- Thompson, J L., The Story of a Photograph, Walker Evans, Ellie Mae Burroughs and the Great Depression. Now and Then Reader LLC., 2012.

- Raines, H., Let Us Now Revisit Famous Folk, New York Times, May 25, 1980.

- Thompson, J L., The Story of a Photograph, Walker Evans, Ellie Mae Burroughs and the Great Depression. Now and Then Reader LLC., 2012.

- Ibid.

- Davidson, C., Let Us Now Trash Famous Authors. The Atlantic, April 2010.

- Rathbone, B., Walker Evans – A Biography. First Mariner Books, 2000.

- Raines, H., Let Us Now Revisit Famous Folk, New York Times, May 25, 1980.

All images have been sourced from the Library of Congress.

Contact Us

Phone: 0421 974 329 (Chris)

Email: write to us!

Newsletter: Subscribe

Web: zebra-factory.com